You Might Have Missed: Drones, U.S. Arms in Iraq, and Civil-Military Relations

More on:

“Unmanned Systems Integrated Roadmap: FY2013-2038,” U.S. Department of Defense, 2013.

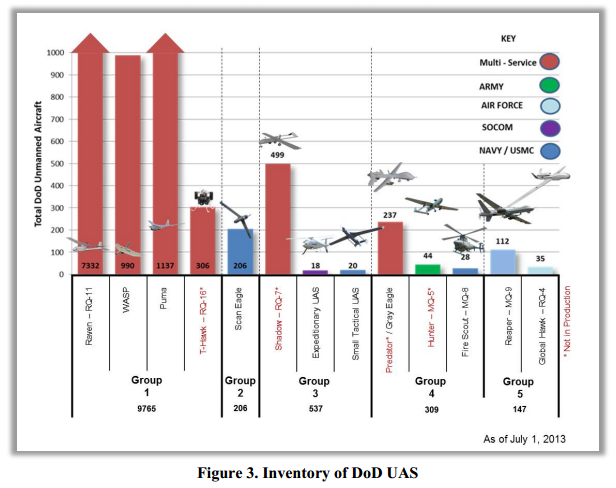

Inventory of DoD UAS (page 5)

(3PA: Like other Pentagon reports, the data contained in this chart should be treated with some skepticism. In May, the Pentagon provided its Annual Aviation Inventory and Funding Plan to Congress. That report listed the total Department of Defense aircraft fleet as being composed of 14,776 aircraft, but did appear to include some of the tactical surveillance drones listed above. This chart also presumably does not include the Central Intelligence Agency’s drone fleet, which according to Greg Miller consists of some 30-35 weapons systems.)

2.4.1 Autonomy (page 15-16)

The potential for improving capability and reducing cost through the use of technology to decrease or eliminate specific human activities, otherwise known as automation, presents great promise for a variety of DoD improvements. However, it also raises challenging questions when applying automation to specific actions or functions. The question, “When will systems be fielded with capabilities that will enable them to operate without the man in the loop?” is often followed by questions that extend quickly beyond mere engineering challenges into legal, policy, or ethical issues. How will systems that autonomously perform tasks without direct human involvement be designed to ensure that they function within their intended parameters? More broadly, autonomous capabilities give rise to questions about what overarching guiding principles should be used to help discern where more oversight and direct human control should be retained.

The relevant question is, “Which activities or functions are appropriate for what level of automation?” DoD carefully considers how systems that automatically perform tasks with limited direct human involvement are designed to ensure they function within their intended parameters. Most of the current inventory of DoD unmanned aircraft land themselves with very limited human interaction while still operating under the control of a human and perform this function with greater accuracy, fewer accidents, and less training than a human-intensive process; as a result, both a capability improvement and reduced costs are realized. This specific automatic process still retains human oversight to cancel the action or initial a go-around, but substantially reduces the direct human input to one of supervision. Human-systems engineering is being rigorously applied to decompose, identify, and implement effective interfaces to support responsive command and control (C2) for safe and effective operations.

Systems are designed and tested so that they perform their tasks in a safe and reliable manner, and their automated operation must be seamless to human operators controlling the system. This automation does not mean operators are not monitoring the control of the system. Currently, automated functions in unmanned systems include critical flight operations, navigation, takeoff and landing of unmanned aircraft, and recognition of lost communications requiring implementation of return-to-base procedures. As technology matures and additional automated features are thoughtfully introduced, DoD will continue to carefully consider the implications of autonomy…

Michael R. Gordon and Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Sends Arms to Aid Iraq Fight With Extremists,” New York Times, December 25, 2013.

“We have not received a formal request for U.S.-operated armed drones operating over Iraq, nor are we planning to divert armed I.S.R. over Iraq,” said Bernadette Meehan, a spokeswoman for the National Security Council, referring to intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance missions. For now, the new lethal aid from the United States, which Iraq is buying, includes a shipment of 75 Hellfire missiles, delivered to Iraq last week. The weapons are strapped beneath the wings of small Cessna turboprop planes, and fired at militant camps with the C.I.A. secretly providing targeting assistance…

(3PA: For more on Iraq’s unofficial requests for U.S. drone strikes, and for President Obama’s correct decision to refuse them.)

Barton Gellman, “Edward Snowden, after months of NSA revelations, says his mission’s accomplished,” Washington Post, December 23, 2013.

At the Aspen Security Forum in July, a four-star military officer known for his even keel seethed through one meeting alongside a reporter he knew to be in contact with Snowden. Before walking away, he turned and pointed a finger.

“We didn’t have another 9/11,” he said angrily, because intelligence enabled warfighters to find the enemy first. “Until you’ve got to pull the trigger, until you’ve had to bury your people, you don’t have a clue.”

(3PA: This is a disturbing conception of how civil-military relations are supposed to work in the United States, and one you rarely hear from senior military officials. The idea that only those in uniform—and in particular “trigger-pullers,” or those in mortuary affairs—are allowed to have opinions about sensitive military programs is preposterous, and an attack on the principle of a civilian-led military as established in Article II, Section II of the U.S. Constitution.)

Mark Thompson, “The Navy’s Amazing Ocean-Powered Underwater Drone,” Time.com, December 22, 2013.

The Navy has been seeking—pretty much under the surface—a way to do underwater what the Air Force has been doing in the sky: prowl stealthily for long periods of time, and gather the kind of data that could turn the tide in war.

The Navy’s goal is to send an underwater drone, which it calls a “glider,” on a roller-coaster-like path for up to five years. A fleet of them could swarm an enemy coastline, helping the Navy hunt down minefields and target enemy submarines…

More on:

Online Store

Online Store